Museums, historical attractions, restaurants and special events recognize ethnic groups who came from the Old World to settle in America

Pride of heritage runs deep and wide in Wisconsin, where the largest and smallest of communities demonstrate ongoing devotion to their European roots.

Ninety percent of the state’s population is of northern European descent. Many of the beloved foods, traditions and ways of life that immigrants brought to Wisconsin during the mid 1800s continue as reminders of cultural identity today.

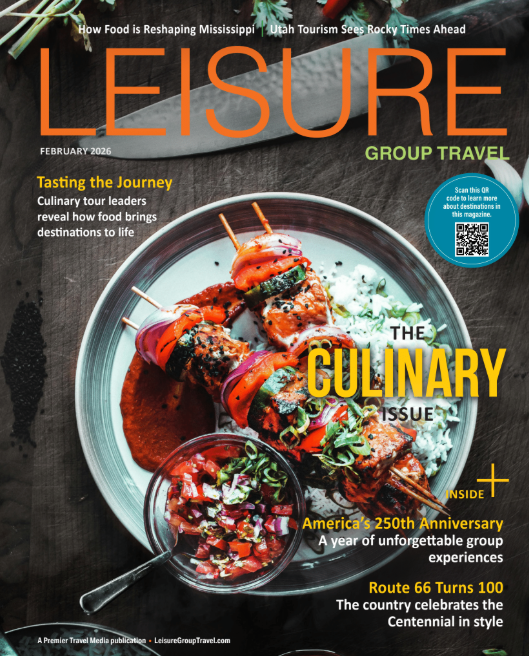

The official state pastry, kringle, is a flaky oval with fruit or nut filling. Wisconsinites love the labor-intensive treat from Denmark because Racine bakers made it their specialty generations ago. The Lake Michigan city also is home to Wells Brothers, in the same modest neighborhood since 1921 and arguably the oldest Italian restaurant in the state.

Most prevalent, statewide, is German ancestry. About 40 percent in Wisconsin say they are of German descent. That means authentic German meals, beer and events are easy to find.

One of the Midwest’s largest and longest-running Oktoberfest celebrations began in La Crosse in 1961. Staged for four days at two fest grounds in late September and early October, Oktoberfest USA features carnival rides, wiener dog races and two parades. The Milwaukee area abounds with Oktoberfests, but the big one is in Glendale on September weekends and the first weekend in October in Heidelberg Park at the Bavarian Bierhaus.

German food? Schnitzel, rouladen, sauerbraten and sausages are on the menu at Dorf Haus in unincorporated Roxbury, 25 miles northwest of Madison’s lively Essen Haus, where oompah music and polka dancing are business as usual on Friday and Saturday nights.

Raspberry is just one of many kringle flavors to enjoy from Racine bakers.

A mural depicts the Rhine riverbank’s Lorelei Rock at Lorelei Inn in Green Bay, where German beer was on tap years before becoming fashionable. At OB’s Brau Haus, Appleton, imported German ingredients are used to brew beer locally. Al and Al’s Steinhaus, Sheboygan, began as a corner neighborhood tavern that grew to add German-specialty dining decades ago.

The 1902 Mader’s, in downtown Milwaukee, is the city’s oldest restaurant. Mader’s serves beer by the glass boot and repeatedly ranks among the city’s best destinations for ethnic dining. Old World reminders – ornate woodwork, stained glass, sense-of-place paintings and murals – are abundant at Kegel’s Inn in suburban West Allis, a longtime restaurant and beer hall with seasonal outdoor beer garden.

Traditional German-influenced architecture can be found throughout Milwaukee. Downtown’s magnificent 1894-1896 Milwaukee City Hall building, a prime example, is the only American city hall constructed in the German Renaissance Revival style and with its 393-foot clock tower is an iconic part of the city’s skyline. The massive municipal building was shown in the opening credits of the TV series “Laverne & Shirley,” which was set in Milwaukee.

As winter nears, the annual International Holiday Folk Fest draws thousands to State Fair Park, West Allis, for an indoor celebration of nations that includes much of Europe. Children and adults dance onstage in attire traditional to their native land. Students are rewarded for visiting booths that teach international culture and history. Shoppers buy Polish pottery to Ukrainian Easter eggs, nibble on French crepes, Czech dumplings, Italian cannoli.

The European Village and Streets of Old Milwaukee exhibits at the Milwaukee Public Museum capture the history of the European people that settled and populated Milwaukee in its early days. Furnishing the re-created homes and shops at the European Village are folk art, costumes, musical instruments and other artifacts that represent 33 cultures, including Austrian, Belgian, Croatian, Irish, Polish, Ukrainian, Welsh, Hungarian, Portuguese, Latvian, Lithuanian, the list goes on.

A look inside one of the European Village homes within the Milwaukee Public Museum.

Another Milwaukee gem is the Grohmann Museum, touted as having the “most comprehensive art collection dedicated to the evolution of human work.” Most of the 1,700-plus paintings, sculptures and works on paper are European (from 1580 on), with most of the paintings by Dutch and German artists. The art is arranged by work themes, such as medical, mining, farming and metal processing. The Grohmann Museum is on the campus of MSOE University.

Several historical sites in Wisconsin pay homage to European roots, too. At Norskedalen Nature & Heritage Center (the name means “Norwegian Valley”), 20 miles southeast of La Crosse, museum galleries and preserved buildings reveal how long-ago immigrants lived and worked. Groups can enjoy a catered Norwegian meal and hike the miles of trails through wooded bluffs.

Pendarvis preserves the relics and buildings of Cornish lead miners in Mineral Point, a small community whose historic district was Wisconsin’s first on the National Register of Historic Places. On the 600-acre Old World Wisconsin campus, near Eagle, are 60 historic structures that were relocated, restored and staffed with living history interpreters; many buildings were the work of Danish, Finnish, German, Norwegian and Polish immigrants.

A melting pot of nationalities is engrained into the Door County peninsula’s identity. Al Johnson’s Swedish Restaurant, Butik and Stabbur is a favorite stop for travelers to Sister Bay – especially since goats graze on the sod-topped roof during much of the year. On the menu: thin pancakes topped with lingonberries, grilled sandwiches served on limpa bread, pickled herring, Swedish meatballs.

Ephraim was settled by the Norwegian Moravian faith community, and volunteers lead guided history tours that explain how the past is a part of present-day life. Signs of Icelandic history are evident in architecture and museums on Washington Island; a short ferry ride away is Rock Island State Park, whose Boat House library is richly furnished with elaborate, hand-carved furniture made by Icelandic and Scandinavian ancestors.

Elsewhere in Wisconsin are hamlets that make up for their small population with a huge respect for their motherland. One nickname for Hurley, in the far north, is “Little Finland,” and this is where the National Finnish American Festival Cultural Center is a keeper of heritage.

Cow statue outside of the beautiful Chalet Landhaus in New Glarus, Wisconin.

Stoughton, in Dane County south of Madison, hosts a mid-May, multi-day Syttende Mai festival in honor of Norwegian independence. What else? A local bakery makes lefse all year, fiddlers perform with Norway’s national instrument (the Hardanger) and Livsreise thrives as a Norwegian heritage center that tells the story of Norwegian immigration to Wisconsin from 1825-1910. High schoolers perform in a Norwegian dance troupe, the Edvard Grieg men’s chorus is nearly one century old, and a state rosemaling association arranges classes, exhibits and sales.

Also south of Madison is New Glarus, home to the Swiss Center of North America, which tells and preserves stories of Swiss immigration in the U.S. and Canada. The Swiss Historical Village & Museum chronicles Swiss pioneer life in 14 artifact-filled buildings, including a settler’s cabin, school, blacksmith shop, bee house and church. New Glarus, a town of only 2,266 residents, is large enough to turn festivals into something special because of a vjodlerklub (choir of yodelers) and meters-long alphorns (used to call home cattle, long ago). Other annual offerings include Heidi and Wilhelm Tell festivals (in June and September, respectively). Noticeable all year: alpine chalet architecture, walnut and almond horns at New Glarus Bakery, rich fondues and rosti potatoes at Chalet Landhaus.

Belgium, population 2,421 and in Ozaukee County, is home to the Luxembourg American Cultural Society, a combination museum, genealogy center and headquarters for cultural programs/assistance. Luxembourg’s grand duke and prime minister have visited. The motherland trusts only this facility in the U.S. to assist with dual-citizenship requests, and about 3,000 families were assisted from 2009 through 2022. One family surname is honored during Luxembourg Fest Week in August, which turns the event into somewhat of an international reunion.

Regardless of community size or the part of Wisconsin visited, much remains to recognize history and homelands that are far beyond the state’s borders.

By Mary Bergin

Main image: Inside Milwaukee’s Grohmann Museum