Exploring the role of Black residents and their contributions to Fredericksburg history

By Dave Bodle

The Thirteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution was passed in 1865 forever abolishing slavery. If the former Confederate states like Virginia were to regain federal representation, they needed to ratify the Thirteenth Amendment. The timeline for the Fredericksburg Civil Rights Trail begins in 1865 and continues to the present. As is the history of our country, freedom is a work in progress.

Enough cannot be said about the partnership between the City of Fredericksburg and University of Mary Washington. The authors of the trail’s narrative are Victoria Matthews (City of Fredericksburg Economic Development and Tourism) and Chris Williams (University of Mary Washington’s James Farmer Multicultural Center). The University Geography Department and Historic Preservation Department students and faculty made significant contributions developing the story maps, collecting oral histories and archival information.

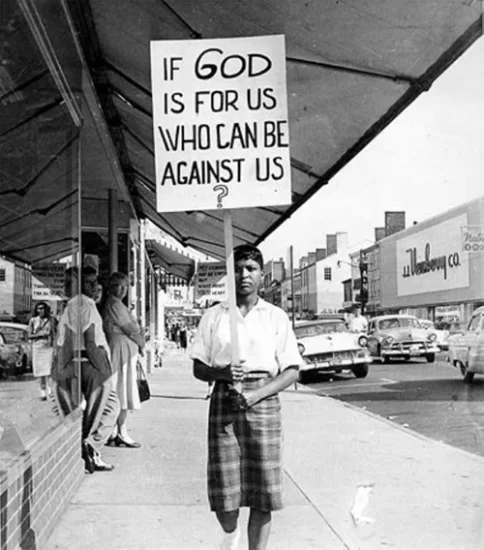

Freedom Riders Marker Dion Diamond Freedom Rider in the City of Fredericksburg

Overview of Fredericksburg Civil Rights Trail

There are two parts to the Fredericksburg Civil Rights Trail. Part 1 is a 2.5-mile walking tour through Fredericksburg’s historic downtown. Begin at the Fredericksburg Visitor Center where you can pick-up a walking tour map and The Negro Motorist Green Book, used during segregation from 1936 through 1968. There are 12 stops on Part 1 of the Civil Rights Trail. Part 2 also begins at the Visitor Center and continues with four stops on the campus of University of Mary Washington with .5-miles of walking and the remaining two stops accessed by 1.9-miles driving. There are oral history recordings on both Parts.

Travel Group Options in Fredericksburg, VA

Large groups preferring to walk Part 1 can be divided making the experience more manageable. The Civil Rights Trail is not chronological. If a windshield tour is preferred, a guide can be provided and the route adjusted.

Rev. B. H. Hester, Shiloh Baptist Church

Fredericksburg, Virginia Civil Rights Attractions

Shiloh Baptist Church (Old Site)

Shiloh Baptist Church pastors and numerous Black citizens of the congregation were critical in the struggle for social justice. Reverend George Dixon was highly respected and one of 24 Blacks attending the Virginia Constitutional Convention in 1868, enfranchising freedmen, reform local government and establish a state-wide system of free, public education. Reverend B.H. Hester was a strong advocate of education. The church dedicated money for the regions only school for Black students where he served as teacher and coach.

Dr. Philip Y. Wyatt, Sr. was a dentist and member of Reverend Hester’s congregation. His commitment to the fight for civil rights in Virginia elected him in 1953 president of the NCAAP’s Virginia State Conference. He co-chaired the Fredericksburg Biracial Commission and was a member of the Virginia State advisory Committee to the U.S, Commission on Civil Rights. You’ll find more of his story on Part 2 of the tour.

In July of 1960, the church served as a training site for students preparing for the segregated lunch counter and movie theaters sit-ins that would take place in downtown Fredericksburg. Dealing with physical and verbal abuse by white residents was the focus of their training. More on the sit-ins are found at Stop 3 of this Trail.

Colored Cemetery at Potter’s Field

This was the site enslaved and free Black people were laid to rest from the 1800s and early 1900s. It was not unusual for Black cemeteries to be moved to make room for development. The Fredericksburg cemetery was no exception. (Moved to Shiloh Cemetery. Part 2 Trail) The cemetery became the site for a new high school. In 1920 the all-white Murray School was built. It served as Fredericksburg’s white high school until 1952 and as an elementary and middle school through 1979.

Removing the bodies from their resting place and building a segregated school on that space is tragic. However, the story of one student’s experience during desegregation is captivating. Robert Christian, still a resident of Fredericksburg, remembers the hostility he encountered as a Black student when the Murray School was first desegregated. Entering the classroom, he recalls the kids whispering and the teacher directing him to sit in the back of the class. One thing Robert says he’ll never forget is the lunch room. Sitting at the lunch table everyone got up and moved.

An uncle had talked to young Robert explaining he’d be called names, but not to talk back.

Shiloh Cemetery Gates

Former Greyhound/Trailways Bus Station

The bus station was located on the site where the fire department building now stands. The bus station segregated the establishment with “White” and “Colored” facilities. On the site is a Virginia State Historical Marker dedicated to the Freedom Riders.

The Freedom Riders were orchestrated by civil rights activists, Dr. James Farmer. (More on James Farmer Part 2 Civil Rights Trail.) The purpose was to challenge segregation of interstate travel. The Fredericksburg bus station was the first stop. On May 4, 1961 a group of 13 Freedom Riders arrived and entered the bus station without incident. Accompanying Farmer were James Peck, Genevieve Hughes, Joe Perkins, Walter Bergman, Frances Bergman, Albert Bigelow, Jimmy McDonald, Ed Blankenheim, Hank Thomas, Charles Person, Reverend Benjamin Elton Cox and John Lewis. Although the group encountered no hostility in Fredericksburg as their journey south continued they faced huge resistance and shameful atrocities from white people and the Ku Klux Klan.

Jerine Mercer on the Civil Rights Trail in Fredericksburg, VA

Fredericksburg, VA Civil Rights Destinations

Much of this story deals with the desegregation of Mary Washington College. In 1954 the U.S Supreme Court ruled unanimously in Brown v. Board of Education that state sanctioned segregation of public schools was a violation of the 14th amendment. By extension this applied to colleges and universities, but it was not until ten years later that the college’s Board of Visitors formally approved a desegregation policy.

Combs Hall

After being rejected from the University of Virginia’s pre-med program, Venus Jones was accepted at Mary Washington College (now University of Mary Washington) as the second Black residential student. During her time at the college she was one of five Black female students.

In 1968, she graduated with a Chemistry degree and four years later graduated from the University of Virginia medical school. The only Black woman to graduate she did her medical internship with the Native American population in Phoenix, Arizona. Joining the United States Air Force, she later became a consultant for the United States Surgeon General.

Dorothy Hart Community Center

The year was 1950 and the Walker-Grant High School graduating class wanted to use the Community Center that was customarily used by Whites. Advised by Dr. Philip Wyatt, Sr, senior class president James Walker accompanied by R.C. Ellison the school’s PTA president approached the city. Permission was initially refused, but later allowed with the condition that students and attendees enter and exit through a side door near the rear of the building.

James Walker declared he would rather receive his diploma on the sidewalk and with Dr. Wyatt and Mrs. Ellison a protest plan was organized. The 27 students in their caps and gowns were joined by almost 300 additional protesters on commencement day. They held large signs saying, “These doors are closed to us,” sang and heard Dr. Wyatt deliver a speech that the students were “learning at the outset that life is filled with problems.”

For additional information and group scheduling call Victoria Matthews at 540-372-1216, or email vamatthews@fredericksburgva.gov Additional information can be found online at fxbg.com/civil-rights-trail/