Libraries and literary points of interest appeal to culturally minded travelers looking to ferret out some of the city’s under-the-radar gems

Call me a nerd or label me a bookworm, but I’ve always felt at home in libraries, those quiet, secure refuges brimming with bound volumes and populated by studious patrons and helpful people behind the desks. There I find peace and order and seem to come away smarter simply by osmosis.

As a traveler, I’m always looking for the less obvious sights, not the ones on everyone else’s checklist. Being a big fan of New York City but having seen the Statue of Liberty, Empire State Building and other high-profile attractions more than once, I made a point of digging a little deeper on my most recent trip and decided to follow my passion for the printed word and theme it along literary lines. My base of operations: The Library Hotel, where each of the 10 guest room floors is dedicated to one of the 10 major categories of the Dewey Decimal System. Every guest room has its own collection of books and art exploring a topic within the category. Located at Madison Avenue and East 41st Street, the cozy nest is a book lover’s paradise and just minutes from one of the world’s great libraries.

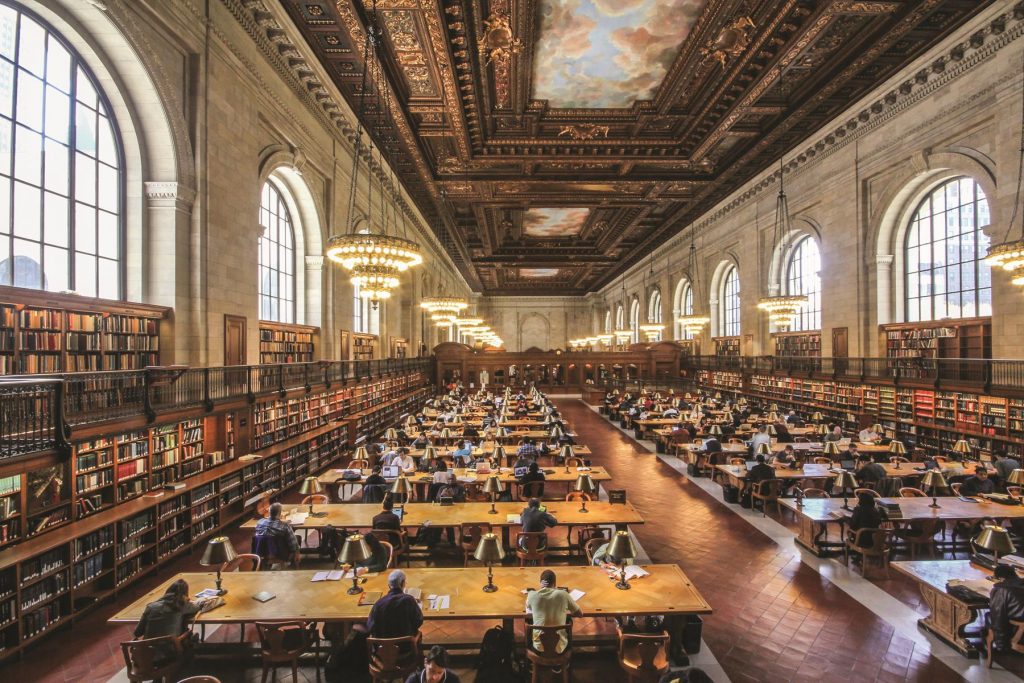

The New York Public Library’s magnificent Rose Main Reading Room

From my hotel room I could see the stately Fifth Avenue facade of the iconic flagship of the New York Public Library. Called the Stephen A. Schwarzman Building, it’s part of a network that includes 88 branches in Manhattan, the Bronx and Staten Island. One of the system’s four research centers, with renowned collections in the humanities, social sciences and fine arts, the masterpiece of Beaux-Arts architecture awes visitors with its majestic public spaces, which can be enjoyed on a free docent-led tour. (Check with the library about the availability of tours during the pandemic.) A 23-minute film about the library also provides good orientation (and likely will resume screenings once the current health crisis subsides).

New York Public Library

The tour highlight is the third floor’s Rose Main Reading Room, nearly the length of a football field. A celestial ceiling mural and massive windows overlooking the 42 oak tables give the room a jaw-dropping grandeur. Nearby, murals illustrating the history of the recorded word adorn the McGraw Rotunda. Among those depicted in the murals (funded by the Depression-era Works Progress Administration) are Moses with a stone tablet bearing the Ten Commandments and printing-press inventor Johannes Gutenberg with a Bible, the first substantial book created in the West with moveable metal type.

Also featured on the tour: Astor Hall, the palatial lobby noted for its expanses of white marble, soaring arches, intricately carved wood and two broad staircases; DeWitt Wallace Periodical Room, with its richly paneled walls and murals of the historical headquarters of great New York publishing houses; and the Map Collection room, one of the world’s largest repositories of maps, atlases and globes. An exhibit on the ground floor’s Children’s Center preserves the well-worn stuffed animals that inspired British writer A.A. Milne’s Winnie-the-Pooh stories. Artifacts and photos in the building’s other display cases tell the library’s story.

Outside on Fifth Avenue, visitors pose for photos next to one of the marble lions guarding the entrance of the building, which was dedicated by President William Howard Taft on May 23, 1911, and hailed then by the New York Herald as “a splendid temple of the mind.” At the time it was the largest marble building in the country.

The library’s shop has the perfect gifts for bibliophiles, from bookmarks to scarves. One canvas bag for sale is inscribed with these words from Cicero: “If you have a garden and a library, you have everything you need.”

The New York Public Library shares a city block with bustling Bryant Park, a midtown Manhattan gathering spot not far from Times Square. The park has indoor and outdoor restaurants, food kiosks, gardens, chairs and tables, a carousel, a lawn for sunbathing and picnicking, areas for chess and ping pong, and free music and dance performances. In winter, the lawn becomes a free-admission ice-skating rink. Among those honored with monuments are author and poet Gertrude Stein, German writer and statesman Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, Mexican national hero Benito Juarez, and poet and civic reformer Willian Cullen Bryant, for whom the park is named.

Beneath the surface of Bryant Park, the library houses millions of books, which are retrieved from the stacks by an archaic dumbwaiter system. Since this is a research library, books never leave the building.

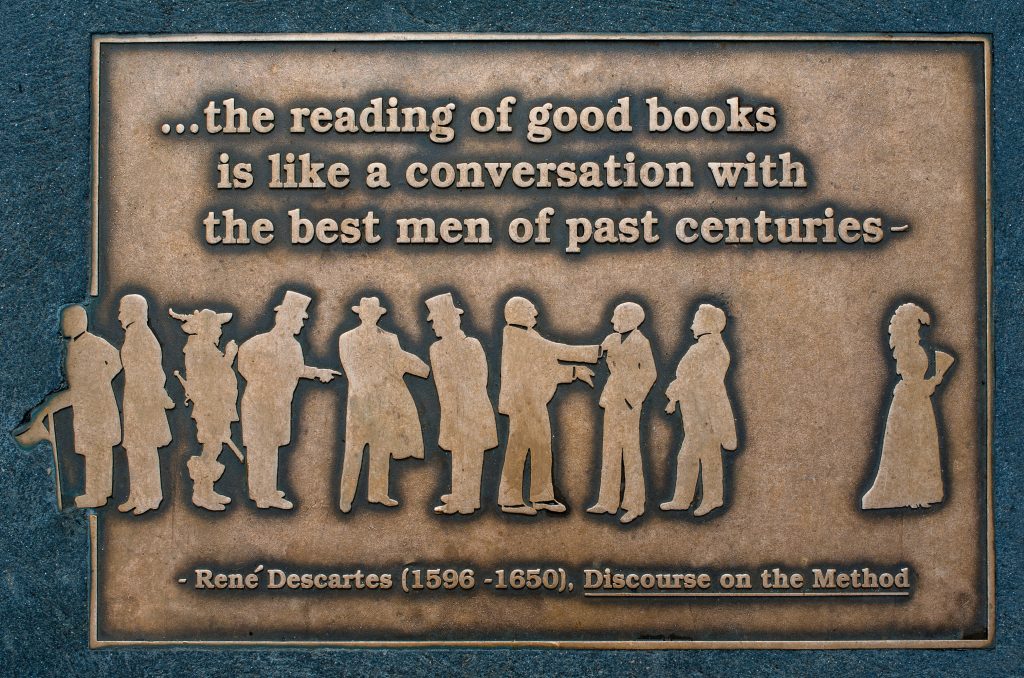

Library Way

Street signs and red-and-white banners on the two-block stretch of 41st Street between the library’s front steps and Park Avenue declare the promenade as Library Way. Bronze sidewalk plaques, placed at regular intervals, celebrate the written word with quotations, verses and literary passages from famous authors, poets and thinkers—not that many tourists or locals take notice of them as they hurry on their way.

The Library Hotel, a 14-story brownstone dating from 1900, stands at the heart of Library Way, which is visible not only from guest rooms but from the second-floor lounge where breakfast is served. In the small, unassuming lobby furnished with bookshelves, a wall of replica card catalog drawers back the front desk.

Breakfast is served in the Library Hotel’s second-floor Reading Room, which also hosts an evening wine and cheese reception.

On my recent stay, I occupied the Ancient Language room on the fourth, or Language, floor. My bookshelves held tomes such as Cassell’s New Latin Dictionary, a Latin version of Milne’s Winnie-the-Pooh, Beowulf, Homer’s The Iliad and The Odyssey, and The History of the Ancient World. A framed painting showed the detail of a house ruin in Pompeii. Around the room were inspirational quotations like: “I have always imagined that Paradise will be a kind of library,” a thought expressed by Argentine writer Jorge Luis Borges. The oblong throw pillow had this message: “Book lovers never go to bed alone.”

Down the hall were the Slavic, Middle Eastern, Romance, Asian and Germanic language rooms. Each of the 10 floors has six rooms, and guests may request a specific one. Perhaps you want the Political Science room on the Social Science floor or Biography room on the History floor. On the eighth floor, dedicated to Literature, choices include Mystery, Fairy Tales and Erotic Literature. Once I stayed in the Computers room on the Technology level, where nearby quarters were named Medicine, Health & Beauty and Management. Each of the 60 guest rooms has anywhere from 50 to 150 books pertinent to the subject at hand.

Literary references extend to the boutique hotel’s rooftop Bookmarks Lounge, an indoor/outdoor space whose menu lists specialty cocktails like Tequila Mockingbird (Sauza Blue tequila, agave nectar, fresh lime juice, minced ginger) and Dante’s Inferno (mezcal, blood orange liqueur, Aperol). Catcher in the Rye combines Sagamore rye whiskey with angostura and lavender bitters, while the F. Scotch Fitzgerald is made with Glenmorangie 10 Year single malt scotch. The hotel’s on-site restaurant, Madison & Vine, has sidewalk tables for warm-weather dining right next to the bronze plaques of Library Way.

When there is no pandemic putting a monkey wrench into normal operations, the second floor’s book-lined Reading Room normally features a continental breakfast buffet (oatmeal, hard-boiled eggs, fresh fruit, juices, Danish, scones, mini-muffins, croissants, bagels with cream cheese, yogurts and other goodies) and a three-hour wine and cheese reception each evening. The clubby room is open 24 hours, with coffee, tea, fruit, pastries and cookies always available. Besides the bookshelves, a nice touch is the open Webster’s unabridged dictionary on the grand piano.

Library Way Plaque

The Library Hotel is one of four Manhattan boutique properties in the Library Hotel Collection, which also has properties in Budapest and Toronto. (www.libraryhotelcollection.com)

Heading east on Library Way, a project of the New York Public Library and Grand Central Partnership neighborhood organization, takes you to within a block of Grand Central Terminal, an architectural jewel and a beehive of activity in midtown Manhattan for more than a century. Saved from the wrecking ball in the 1970s, the 1913 Beaux-Arts train station at 42nd Street and Park Avenue is worth exploring on a self-guided audio tour or a 75-minute tour with a docent from the Municipal Arts Society, though these tours have been temporarily suspended because of the coronavirus.

The most notable feature of the Main Concourse is the massive vaulted ceiling and its astronomical mural painted in gold leaf on cerulean blue oil. The painting portrays the Mediterranean sky with medieval-style zodiac signs and 2,500 twinkling stars. The Dining Concourse, a labyrinthine food court filled with railroad memorabilia and decor, abounds with specialty restaurants and tempting bakeries. People flock there for everything from curries and cupcakes to chili, deli sandwiches and spicy Jamaican beef patties. For a real New York experience, dine under the tiled-vaulted ceilings of the Oyster Bar, which offers fresh seafood, including 30 varieties of oysters at its raw bar.

The landmark station is the major stop on the 90-minute neighborhood walking tour that was offered at 12:30 p.m. every Friday by the Grand Central Partnership (until the coronavirus struck and caused its suspension for the time being). On a visit to New York in January, I was able to take advantage of this weekly freebie, which also included the lobby of the Chrysler Building and other historically significant sights big and small.

Those on the lookout for quirky attractions will want to visit the American Kennel Club’s Museum of the Dog, my favorite new discovery in the Grand Central district. Formerly in St. Louis, the museum last year returned to AKC headquarters in Manhattan. The updated museum’s interactive stations include Find Your Match, a digital board that matches your face to a dog breed, and Meet the Breeds, a touchscreen that lets guests explore the history and traits of different breeds. The museum also features paintings, figurines and sculptures of man’s best friend. Dog lovers will like the gift shop.

Getting back on the literary track, let’s pop into the historic Algonquin Hotel, located at West 44th Street between Fifth and Sixth avenues, a short walk from Times Square or Grand Central Terminal. The 12-story hotel, which opened its doors in 1902, pegs its fame to the Algonquin Round Table, a group of writers, critics, artists and theatrical elites who met there every day for lunch and stimulating conversation in the 1920s. A plaque by the hotel entrance, designating the Algonquin as a literary landmark registered by the Friends of Libraries U.S.A., lists some of the literati—Dorothy Parker, Robert Benchley, New York Times theater critic Alexander Woollcott, Harold Ross (founder and editor of The New Yorker), William Faulkner, Sinclair Lewis, Gertrude Stein, James Thurber—who “found a haven within its oak-lined walls.” To soak in a bit of the history, stop in for a drink under the blue glow of the famous Blue Bar. Perhaps you’ll spot Hamlet, the resident cat who represents a long lineage of felines who have lived at the hotel since 1923.

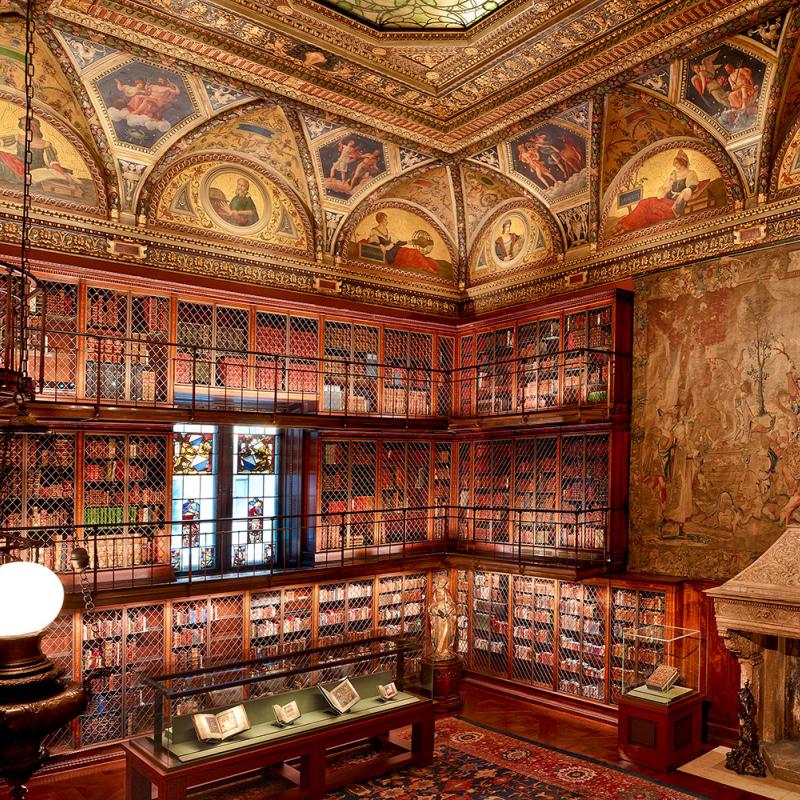

Morgan Library

In the Murray Hill neighborhood of Midtown East, a short walk from Grand Central Terminal, resides the Morgan Library & Museum, one of New York’s great overlooked gems. The legacy of Gilded Age financier J.P. Morgan (1837-1913), it is a treasure house of rare manuscripts, artwork and ancient relics. On display in Mr. Morgan’s original three-story library, with its inlaid walnut bookshelves and magnificent ceiling, is one of the institution’s three Gutenberg Bibles and a rotating collection of other artifacts. On any given visit, you might see illuminated medieval manuscripts, drawings by Leonardo da Vinci, musical scores by Beethoven or Mozart, or letters written by U.S. presidents. (Many items were purchased by Morgan on his world travels, but others were acquired by the library after his death, so don’t be surprised to see correspondence from John F. Kennedy or Martin Luther King, Jr.) A visit to Morgan’s personal library and study, a lordly room covered in red brocaded wallpaper, includes a peek into the vault where the wealthy tycoon kept his most valuable pieces.

A central, piazza-style atrium created by famed architect Renzo Piano, part of a 2006 expansion that doubled exhibition space, links the original 1906 library and 1928 Annex to an 1852 Italianate brownstone, the home of J.P. Morgan, Jr. from 1905-1943. The residence, at the corner of Madison Avenue and 36th Street, houses the museum shop and restaurant.

The Garden Court was designed by John Russell Pope to replace the open carriage court of the original Frick residence. The Court’s paired Ionic columns and symmetrical planting beds were echoed in Pope’s later designs for the original building of the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C.

The Fifth Avenue mansion of industrialist Henry Clay Frick, another Gilded Age patron of the arts, has the same appeal as the Morgan and displays some of the art from the Morgan estate. While the adjacent Frick Art Reference Library is open only to those doing art history research, the historic house turned museum—known as The Frick Collection—is one of New York’s great under-the-radar attractions, providing an intimate setting for viewing Old Masters paintings, antique furniture and decorative arts (though it has been closed during the coronavirus pandemic). Built from 1912-1914 by Hastings and Carriere, the firm that designed the New York Public Library 25 blocks away, the home occupies the site of the private Lenox Library, torn down in 1905. One of the lavishly furnished rooms, with a portrait of George Washington by Gilbert Stuart, is Mr. Frick’s personal library.

The shady paths of Central Park lie just across the street from The Frick, and there we find the Mall Literary Walk, with a collection of statues of celebrated men of letters, including Sir Walter Scott, Robert Burns and William Shakespeare.

Just walking around Manhattan you’ll run into other places with literary connections. Last year, for instance, I stayed at the Hotel Giraffe (another member of the Library Hotel Collection) at Park Avenue South and 26th Street and noticed an honorary street sign recognizing the intersection as Herman Melville Square. A plaque nearby indicates that the author of Moby Dick lived at 104 East 26th St. from 1863-1891 in a house (no longer standing) where he wrote Billy Budd, one of his greatest works.

The borough of Manhattan does not have a monopoly on sites of literary interest in New York City. In the Bronx, the Edgar Allan Poe Cottage, a modest white-clapboard farmhouse dating from 1812, is normally open for tours and shows a video about the home where the master of mystery and horror spent his final years, from 1846-1849, but COVID-19 has caused its temporary closure. Furnished with period pieces, the house contains a few personal effects, including Poe’s rocking chair and the bed where his wife, Virginia, died of tuberculosis at age 24. Here he wrote the poems “Annabel Lee” (in memory of his wife) and “The Bells.”

By Randy Mink